Best Of - Write the Shots!

Hey guys,

I loved Billy's recent article called The Movie on the Page. He wrote, "Cinematic storytelling -- the term that's come to define this particular approach to screenwriting -- involves a kind of three-step process (though these steps are often enacted simultaneously): 1) you conceive your story in filmic terms, 2) you see the movie in your head, and 3) you write the story in a language that vividly communicates that movie's sounds and images." Amen and amen! Billy also reminded us of Robert Towne's famous dictum, "When I write a screenplay I'm describing a movie that's already been shot." Exactly.

And so, along these same lines, I wrote this "Write the Shots!" article last November. There is still too much confusion about action lines, about what to write, how much you should write, and fears about "Directing the Director." This madness has to stop. Between this article, Billy's, and Jennifer van Sijll's "Directing the Director," which is referenced below, you should hopefully put this whole issue behind you and you can start to really hone HOW you write your action lines. Believe me, kids, THIS is what master craftsmanship is all about.

-MM

-------------------------------------

Okay, let’s just clear the air of so much bad thinking about action lines. I don’t know how or why this happened, but a lot of newbies seem to think that a scene is comprised of 1) a Master Scene Heading (such as INT. MYSTERY MAN’S KITCHEN – NIGHT) and 2) they should just add some action lines to describe the room, the characters, write a bunch of dialogue, (and quite a few more action lines to describe even the slightest gestures of characters, which we call incidental actions), and 3) move on to the next scene and repeat this process for 120 pages.

Wrong.

How did they get so far away from the core principles of screenwriting? Were they mislead? I don’t know. Even by the very low standards described above, some newbies can’t even get that right and they fill their action lines with what we call unfilmmables – sentences in action lines that are not visual, such as backstories of characters, author’s intrusions, inner thoughts, questions to the reader, etc.

Now, what do we know about action lines? With Trottier’s Screenwriter's Bible, we know that we ARE meant to describe the setting, characters, or actions of those characters, but these sentences must be very lean and mean. We write only what we see on the screen and only the most essential elements using the most minimal words. We have to provide a framework of visuals that tell the story so the reader (and audience) can put two & two together and visualize what's happening on the screen. Action paragraphs should be 4 lines or fewer. You typically write one paragraph per beat of action, and they should be important actions. I loved what Trottier said about incidental actions: “If your character raises her cup of coffee to her lips, that’s not important enough to describe… unless there’s poison in the cup.”

Hehehe...

Always, always err on the side of brevity.

Now let’s take it to the next level. The only way you can truly excel at writing cinematic stories (on a par with or surpassing the pros) is to elevate your craft to a level where you can (without using camera angles) WRITE THE SHOTS.

Bwaaah! You’re SO wrong, Mystery Man! Yes, I can hear you balking already and screaming at your monitors that, dammit, man, you can’t describe the shots because it’s up to the director to decide how that scene will be filmed and thus, all you can do is just tell the story – what happens to what character and then move on to the next scene.

Wrong.

That’s completely and absurdly wrong.

This kind of hands-off thinking about filmmaking has harmed more screenplays, prevented more writers from getting sales, and generally lowered the quality of contemporary films. It’s not enough that we, as screenwriters, must have a god-like knowledge about the story we wrote and about the art of storytelling, characters, dialogue, and structure. Screenwriters are filmmakers, too, and we have to think like filmmakers and endeavor to render our stories CINEMATICALLY, which means that we should write the shots.

This does not, has not, and will not ever offend directors or anyone else. On the contrary, reading a truly visual, cinematic screenplay that really feels like a movie on paper INSPIRES readers, INSPIRES producers, INSPIRES executives, and yes, directors, too, and those are the scripts that GET SALES. I mean, come on. The way to get a director onboard is to get him/her excited about the story and the visuals. And your screenplay is essentially the first grouping of cinematic ideas, the first shot across the bow about how to render this particular story cinematically. It’s the springboard for what will be many future creative discussions about turning your script into a film.

Conflicts between screenwriters and directors have more to do with a screenwriter not thinking like a filmmaker (and wanting to tell instead of show) than it is about a director not recognizing how brilliant the dialogue is. Rules about not writing the shots so as to avoid offending directors are so absurd, because, like everything else in life, this business is about relationships. It's ALL about the relationships you build with people in the business. Period. If you walk into a room and say “this is the way it is and to hell with what you think - no one big or small can change one word or comma of my screenplay,” yeah, everyone will hate you. If, on the other hand, you walk into a room and you're capable of having a creative discourse and engaging people who have different ideas and calmly explaining how and why and what you were trying to accomplish with each moment of your screenplay, you’ll go far. Establishing good, working, creative relationships with people is, umm, a good thing for your career.

With some directors, that’s impossible, but that’s another article.

So let’s talk about writing the shots. I once had a brief conversation about this topic in e-mail with Jennifer van Sijll, a screenwriting professor, consultant, former professional reader for Universal, and author of Cinematic Storytelling. She wrote,

“I think a writer should avoid anything that takes readers out of the read. As soon as they start visualizing equipment rather than what's on the screen, they've broken from the story. Here is an example.

Joe scans the room. His eyes land on the glock. He stops. He trains his eye on the murder weapon, and puts a match to the curtains.

This is a pan, probably a push in to closeup, and a wideshot.

If you can write without mentioning camera angles, it's more engaging.”

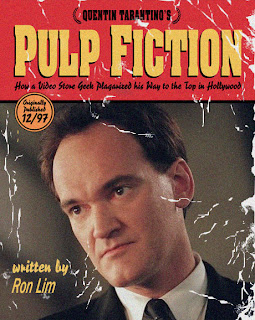

Exactly. She also wrote a great article about this called Directing-the-Director. Here’s a portion in which she discusses a scene from Pulp Fiction. (People always remember Pulp Fiction for it’s great structure and dialogue, but many don’t realize that he also wrote the shots and practically edited each scene through the action lines.)

Cinematic Example: Editing - Pacing and Expanding Time

In the drug overdose scene, midpoint in the movie, Vincent (John Travolta) attempts to revive Mia (Uma Thurman) by stabbing Mia’s heart with a hypodermic needle filled with adrenalin. The scripted scene fills us with tension. We hold our breath hoping that Mia is going to make it.

The reason “we hold our breath” is because the script is written “already edited.” In this case it is edited to “milk the scene” and thereby pump up suspense.

So how does Tarantino do this?

Tarantino does this through overlapping action. He includes cuts to the needle, the red dot, and the faces of characters. These cuts lengthen the time needed for the real-time-event of the stabbing to occur. Although Vincent counts out three seconds on the dialogue track, it takes ¾ of a page for the moment to take place or 45 seconds of screen time. That means that we are holding our breath 15 times longer than Vincent’s three-second countdown suggests.

Through purposeful use of editing, the writer is guiding the reader’s emotional experience, and delivering a scene that can be imagined as a movie.

Writing in Shots

Tarantino accomplishes this by writing in shots. He doesn’t write in descriptive paragraphs like novelists. Each of his sentences implies a specific camera angle. “Implies” is the operative word here. Camera angles and lenses are not called out, but understood from his description.

The script’s pacing mimics what we will later see on screen. Paragraphing and sentence length suggest how long a shot will play on the screen. For example, a single one-sentence paragraph implies one shot. The implication is that it should play out longer on screen than would say, multiple shots implied in a four-line paragraph. The white space buys the single shot time. Adding an editorial aside like “Mia is fading fast. Nothing can save her now” is like saying “hold on the shot”. It again gains the shot more screen time.

Let’s take a look at how this is done in the actual script. This excerpt is taken from mid-scene.

The top line is from Tarantino’s script, where no camera information is given. The parentheticals in the line below are my interpretation of the shot that is implied.

Excerpt from Pulp Fiction

Vincent lifts the needle up above his head in a stabbing motion. He looks down on Mia.

(LOOSE CLOSE-UP VINCENT) (VINCENT POV – MIA)

Mia is fading fast. Soon nothing will help her.

(HOLD ON MIA.)

Vincent’s eyes narrow, ready to do this.

(TIGHT CLOSE-UP – VINCENT)

Count to three.

Lance on his knees right beside Vincent, does not know what to expect.

(WIDE SHOT – LANCE AND VINCENT)

One.

RED DOT on Mia’s body.

(CLOSE ON RED DOT )

Needle poised ready to strike.

(CLOSE ON NEEDLE)

Two.

Jody’s face is alive in anticipation.

(CLOSE-UP JODY)

NEEDLE in the air, poised like a rattler ready to strike.

(CLOSE ON NEEDLE)

Three!

The needle leaves the frame, THRUSTING down hard.

(CLOSE ON NEEDLE)

Vincent brings the needle down hard, STABBING Mia in the chest.

(MEDIUM SHOT)

Mia’s head is JOLTED from the impact.

(CLOSE ON MIA’S HEAD)

The syringe plunger is pushed down, PUMPING the adrenalin out through the needle.

(CLOSE ON SYRINGE PUMPER)

Mia’s eyes POP WIDE OPEN and lets out a HELLISH cry of the banshee.

(CLOSE-UP ON MIA’S EYES)

She BOLTS UP in a sitting position, needle stuck in her chest---SCREAMING

(WIDE SHOT - MIA)

Summary

In this brief page, Tarantino has implied 15 camera angles. Despite his use of camera, the reader isn’t taken out of the read because the script never calls out specific camera positions or angles.

Had Tarantino described the camera angles with 15 descriptors like CLOSE-UP ON MIA’S EYES, it would have been an unbearable read.

Tarantino was able to slow down real time by cutting away to objects and multiple reaction shots of the characters. He used editing and the inherent elasticity of the medium to help dramatize a pivotal moment and up the suspense.

Pacing was further aided by how Tarantino suggested shot length through paragraphing.

I also want to share one more quote from Jennifer’s article:

“Writing cinematically is not the same as Directing-the-Director. Directing-the-director is when you write: “JOE’S POV WINDOW– LOW ANGLE,” instead of “Joe looks up at the window.” They mean the same thing. The first unnecessarily draws attention to camera information taking us completely out of the story. The second method implies it’s a POV shot and a low-angle, but it does not distract us with technical jargon. Similarly if a tracking shot is essential to a scene it’s better to say “Joe jogs alongside Susan” rather than “TRACKING SHOT – JOE AND SUSAN JOGGING which is considered directing-the-director.”

Exactly. I couldn’t agree more.

Consider the “write the shots” example I gave in my Billy Mernit script review. Remember how visual that was? Consider how Melissa Mathison brilliantly incorporated low angles from the creature’s POV in the opening sequence of her E.T. screenplay to make the trucks, the lights, and the keys, all so very scary and to establish the humans as the antagonistic force. Consider the L.A. Riverbed sequence in Chinatown where Gittes follows Mulwray. With Secondary Headings, Robert Towne starts with long shots, then cuts back and forth between Gittes and Mulwray. When the action gets intense, he goes to close-ups of Gittes. Consider the way Apocalypse Now and Barton Fink uses creative camera angles to disorient the audience in order to make a statement about the mental state of the protagonist. You can write that so long as you don't use camera angles. I could go on and on.

Did you know that the world’s first screenplay was written by a woman? Yes, Alice Guy-Blaché wrote “screen-plays” in order to organize her thoughts and all the ways she would experiment with sound and visual effects in the late 1800s. The whole point of her “screen-plays” was to write the shots. By the way, the first screenplay was for a short called The Cabbage Fairy/La Fée aux choux (France, 1896), which was a comic fantasy about babies that were born in cabbage patches. Guy-Blaché would go on to direct over 700 short films and establish one of the world’s first movie studios – Solax.

I don’t mean to say that you have to edit every scene and write every shot with every action line. Sometimes, you just need to write about the action, and yes, the director will figure out how to film it. But write the shots when it really counts. And now you can also take a deep breath and embrace and study all those old screenplays that are full of camera angles. The only thing that’s changed is the fact that we no longer write camera angles, but the principles of action lines have never changed in that we should think like filmmakers, we should render our stories cinematically, and we should write the shots.

-MM

4 comments:

Great post, MM. I started it thinking I'd just give it a quick skim and that maybe I'd re-read in full when I was less busy. I ended up getting sucked in to the point that now I'm commenting. Thanks a lot for ruining my productivity this morning. ;)

McKee makes a similar point in "Story." As screenwriters, we're not to choose the equipment or describe the "technicals" of the shot. We're to describe the visuals in such vivid terms that there's really only one way to shoot it. The Pulp Fiction scene is a perfect example.

Yep.

I was thinking about writing my own addendum to this, but you pretty much covered it.

I think this actually answers my other question.

Christian - a father found the report card his daughter crumpled up and threw away, and forced her to go study?

Post a Comment